Saudi Arabia's Most Important Mega-Project is the Revitalization of its National Identity

Thoughts about my fist visit to the Kingdom, one of the most fascinating—and optimistic—places in the world. And, for the Right in America, there's much to learn from the new Saudi national project.

Saudi Arabia has long been a forbidding place for westerners: austere fundamentalism, lavish oil wealth, and–most confusing of all–Saudis have been both perpetrators and scourges of Islamist terrorism.

While millions of Muslims had always made the religious pilgrimage to Mecca, the Kingdom was never interested in becoming a spot for vacationers, and neglected to issue tourist visas. The expat workers and soldiers who did spend time there lived in their own sealed universes, in bases or luxury hotels and compounds, detached from the experience of typical Saudi life.

Since the ascent of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in 2016, however, the walls separating westerners and Saudis have been coming down. Sight-seeing tourists from Europe and the United States are, for the first time, beginning to trickle into the Kingdom and, due to the recent reforms of religious laws, foreigners are integrating into life in its cities.

The more you think you know about the Kingdom, the more the recent changes will shatter many, if not most, of your preconceived ideas about it. On the other hand, having no expectations would lead you to miss the specialness of what’s taking place. Even as I have followed the region closely for more than two decades, I wasn’t prepared for what I saw there in that desert metropolis. When I traveled to Riyadh last month, Saudis and expats alike enthusiastically attest to how much things have changed, and are still changing, at a rapid pace.

While the Saudi government’s much-discussed Vision 2030 is a comprehensive, society-wide reform project—covering everything from diversification of the economy, with a focus on trade and investment, to public service sectors and the building of infrastructure—perhaps the most visible changes involve the integration of women into Saudi life.

Saudis now routinely attend mixed-gender events; women can drive, go to the gym, and do business without the approval of a male guardian. The sight of the modern Saudi woman—often without the full covering of a traditional niqāb—comes as a surprise for those who recall the religious police (the fearsome Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, known there simply as Hai’a, or “Committee”) reinforcing strict Islamic behavioral codes on both men and women in public and private places.

The Hai’a still exist officially, but have been stripped of their authority to arrest or even confront citizens in public. Saudis of both sexes are still ecstatic about the disappearance of this harsh gender-segregation, allowing a great deal of social freedom, even if that freedom remains circumscribed by conservative conceptions of propriety and modesty.

But the Kingdom understood that authentic social reforms were impossible while the threat of terrorist intimidation from Islamists hung over their citizens—very much including the menacing physical presence of Islamists in their communities.

Since 2017, the young Crown Prince has been increasingly firm in public statements about the Kingdom’s opposition to Islamism. “Seventy percent of the Saudi population is under 30, and honestly we will not spend the next 30 years of our lives dealing with destructive ideas,” he said in 2017. “We will destroy them today, and at once.”

These words were soon backed by swift action, as the Kingdom’s counterterrorism efforts aggressively targeted every type of Islamist—not just violent jihadist cells, but the clerics who inspired them, and the Muslim Brotherhood financiers and journalists who once gave them cover. The authorities smartly retooled NGOs like the Muslim World League, transforming them from their previous mission of promoting Brotherhood pedagogy into instruments of religious pluralism. MbS’s war on extremism was a success, both for the Saudi population and the wider world, as evidenced by the hysteria of western Islamists and their allies in media, think tanks, and governments.

Islamists have become reviled. In sharp contrast to the gangs of long-bearded Salafis now ubiquitous in many other countries (from Cairo to London), most Saudi men today are loathe to take on any of the physical or sartorial characteristics of an extremist; rather, they are well-dressed in impeccably clean thobes and ghutras, and sport tightly-trimmed beards.

These changes are more than just aesthetic; a half-decade later, the level of security outside hotels and other buildings seems non-existent. Just as importantly, though, women now have little to fear from retribution for their choice to expose their hair or face. Western observers have missed the extent to which Saudi Arabia’s counterterror operations and anti-Islamist policies made the social reforms possible.

This economic diversification and the integration of women into society might seem, at first glance, to be a vindication of the forward march of Progress–that, like other once-traditional societies both in the Middle East and elsewhere, Saudi Arabia is finally on the road to modern western libertinism. However, this would be a misreading of the desires of the people as well as the Kingdom’s intentions.

While still monumental, the reforms which are immediately apparent to western observers might be, in the end, not even the most significant. They are pieces in a larger effort: Saudi Arabia’s attempt to navigate the technological and economic advances of 21st Century life while maintaining a measure of their distinct history and culture against a technocrat-led homogeneous Western monoculture that seems to bring with it so much ideologically Progressive baggage.

Thankfully, the Kingdom’s leaders understand that the Muslim world’s answer to its collision with western modernity in the last century—the pan-Islamic identity and its cousin, Islamism—was a dead-end. It doesn’t allow for the personal freedom required to satisfy the population’s desire for higher living standards and a reasonable amount of self-expression, especially between the sexes. And, by necessarily empowering Islamist clerics, it plunges the Kingdom into a fundamentalism that explodes into terrorism both domestically and globally.

The Kingdom’s reforms seemed to reflect Crown Prince’s determination to forge what he called, “a country of moderate Islam that is open to all religions, traditions and people around the globe.” But this is, after all, Saudi Arabia; disempowering the clerics and religious police in order to create space for that moderate Islam creates a vacuum in the traditional Saudi identity, which has been so closely tied to religion since its inception.

To address this, the Kingdom has embarked on a public education project to bolster a robust national identity, one that is not divorced from religion, but is nevertheless separate from it. Saudis are now encouraged to see their part in a vibrant national story that stretches from the early history of Arabia—including, very significantly, pre-Islamic culture—to the modern Saudi state governed by the al Saud dynasty.

That national story is commemorated in a new national holiday on February 22. In only its second year, Saudi Founding Day looks back to Mohammed bin Saud’s ascendancy to power in 1744 , and focuses as well on the role his dynasty has played in the history of Arabia. Prominently displayed in the Founding Day are renderings of Masmak Fortress, site of the 1902 Battle of Riyadh, which saw Ibn Saud’s return from exile in Kuwait and led to the unification of Saudi Arabia under the House of Saud.

Remarkably, this new national holiday is only the second secular holiday in the Kingdom’s history; the other is National Day, which dates back to a 1965 decree and commemorates the 1932 establishment of the modern Kingdom. While they might be difficult to distinguish for outsiders, the difference between the two non-religious holidays is subtle, but important: unlike National Day, which marks a political entity, the new holiday serves to draw citizens closer to the unfolding history and character of the regime itself, from its roots in ancient Arabian culture to its monarchs. In the United States and throughout the west, we have a variety of state holidays; not so in Saudi Arabia, where its Islamic holy days have been inseparable from the identity of the state itself. Adding a second secular national holiday is a significant step, and indicates the importance with which the Kingdom views its new national project.

Luckily, the two-day Saudi Media Forum (which sponsored my visit) coincided with private and public Founding Day celebrations. Unlike well-established civic holidays elsewhere—which have, over decades or centuries, seen their meanings replaced with excuses for commercialism or family get-togethers—the observance of new holidays is usually fairly tentative, as the population has yet to invent its own rituals.

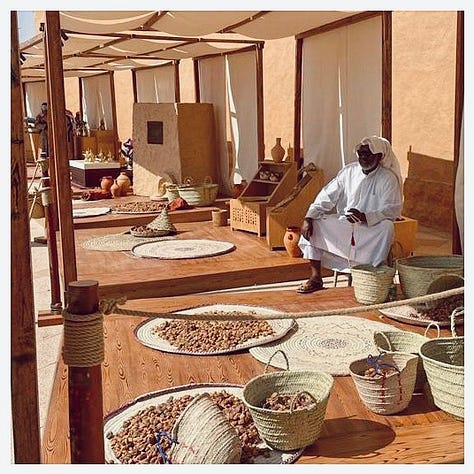

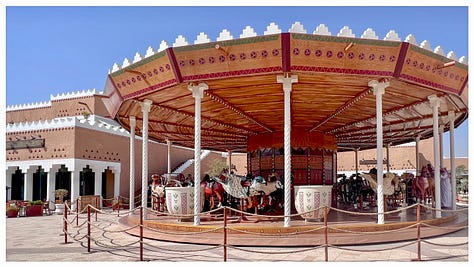

Even as Riyadh was filled with a variety of didactic festivities throughout the week, recreating scenes from Arabia in the 18th Century and the turn of the 20th, it was difficult to discern which displays and events were sponsored by the Kingdom, and which were the result of private initiative and quiet patriotic fervor. In the giant atrium of the nearby mall, crowds gathered in front of a Dior kiosk to witness a dozen men perform traditional Arabian music and dance; coffee shops and stores advertised Founding Day specials; in hotels and museums, visitors were encourage to recreations of the ornate interiors of bedouin tents, with colorful rugs and pillows; artisans explained how Saudi coffee was made in ancient times, mixing crushed and roasted beans with cardamom and saffron.

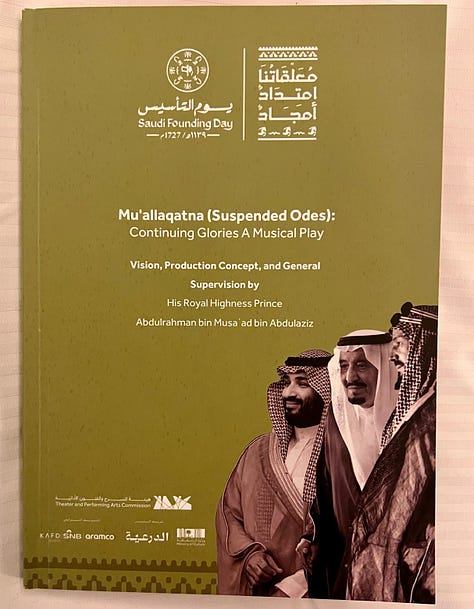

The Saudi Ministry of Culture sponsored a musical as part of the Kingdom’s Founding Day celebrations at a theater at Princess Nora Bint Abdul Rahman University, the largest women’s institution for higher learning in the world. The plot of Our Mu’allaqat: The Extension of Glory concerns a female artist (played by the beautiful Saudi actress, Elham Ali, of the Netflix series, “Whispers”) who had painted portraits of ten early- and pre- Islamic Arabian poets. The night before the opening of her exhibition, the portraits spring to life and, along with the audience, the newly-reanimated poets are treated to the history of Saudi Arabia as told through song. While many of the poems were composed in the 8th Century, others had been beloved in Arabia well before the time of Mohammed.

Even aside from the plot, there was so much about the production that was inconceivable in the Kingdom not even a decade ago: men and women sharing the stage, singing and dancing together, beneath the pulse of loud music roaring from the speakers. This, too, is revolutionary in a country where instrumental music itself is considered haram by Wahhabi Muslims. It was, until recently, if not expressly forbidden by law, then conspicuously absent in public places in order not to offend the religious. There were no longer such concerns, however. As with many of the recent reforms, the Kingdom was making a statement: the production came with the imprimatur of the Kingdom’s royal family, with the script, libretto and original music by Prince Abdul Rahman Bin Musaed and Prince Ahmed Bin Sultan.

What made witnessing the celebrations of Saudi Founding Day fascinating was that it was neither intended for my benefit nor for use as a tool in the Kingdom’s PR effort; it was a holiday—and a larger public education project—expressly for Saudi citizens, intended to deepen their connection with their country. Outreach to foreigners is important to the Kingdom, however, and they’re working on that, too.

The picturesque mountains and wondrous rock formations of AlUla could be mistaken for a luxury desert setting for jet-setting westerners, or the dramatic backdrop for a stream of fashion models, billionaires, and celebrities. Of course, it is that—and, judging from its highly publicized “Winter in Tantora” music and cultural festival in late 2022, it’s clear that the expansive region in the northwest of the Kingdom represents a major effort to attract well-heeled tourists. The biggest attractions of AlUla, however, are the stunning temples carved into giant rocks jutting out of the desert more than 2,000 years ago by the Nabateans, a pre-Islamic Arab people who also built Petra in Jordan.

In promotional material, AlUla is referred to as “undiscovered,” with some justification. Hundreds of years of prior Islamic rulers didn’t merely ignore these ruins of ancient civilizations; most of the world didn’t know they existed at all. Sophisticated excavations and preservation attempts have been ongoing since just 2019, when AlUla was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The AlUla project is only a single example of the Kingdom taking deliberate aim at Islamists’ destruction and erasure of pre-Islamic history and culture. In doing so, they are undermining a foundational Islamist narrative about jāhiliyyah—the “time of barbarism” before the advent of Islam—and a key doctrinal driver for conflict between Muslims and non-Muslims. Islamists’ intolerance of any trace of jāhiliyyah in Muslim-conquered lands required them, they believe, to raze or bowdlerize these pre-Islamic monuments. Among many examples, the Taliban’s infamous destruction of Bamiyan Buddha statues was a well-known modern application of this doctrinal imperative.

Saudi Arabia’s embrace and promotion of the pre-Islamic cultures of the tribes that existed on the Arabian peninsula prior to Mohammed is remarkable and significant, even if it draws fewer headlines or notice by experts in the west. Rather than issuing gauzy press releases about “tolerance,” the Kingdom is engaged in an authentic ideological battle. And the Islamists, losing ground in this fight daily, understand exactly what’s happening.

Certainly, the scale of development in the Kingdom’s largest city is massive, reflecting MbS’ desire to transform it into one of the most livable in the world. Due to the desert climate during much of the year and the old religious barriers to movies, concerts and other activities, Saudi public leisure activities outside the home have consisted mainly of driving to large, indoor malls. Riyadh is creating, for the first time, the infrastructure of common space, including massive parks, riding and walking trails, alongside new theaters, museums, and other entertainment venues.

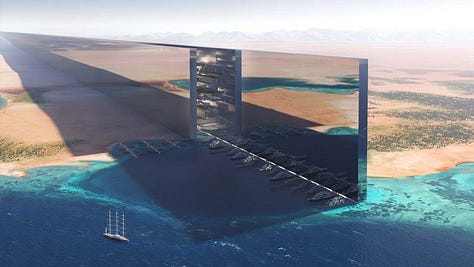

Even more ambitiously, the Kingdom has lately announced gargantuan mega-projects which seek to stuff modern living into a single structure. The Line is an immense, linear, “smart city” which would house 9 million residents in a reflective, mirrored edifice sweeping 110 miles through the desert. The recently announced Mukaab is a perfectly cube-shaped structure the size of five Empire State Buildings which bills itself as “the world’s largest modern downtown.” The clear symbolism of a secular Ka’ba–not in Mecca, but in the Kingdom’s most cosmopolitan city—is certainly intentional. It is an unmistakable, provocative marker in a Saudi Arabia that is changing fast.

In any country, though, the public rarely draws as much pride, optimism and happiness from these kinds of massive works projects, however smartly-designed and ambitious, as do the rulers, the city planners, and the architects themselves. Large-scale projects are imposing structures and, in the Middle East and Asia, nearly always rely on credentialed celebrity foreign architects and established design firms in North America or Europe. These centerpieces are often tasteful yet provocative by design; they are intended to set themselves apart from the environment and other, more commonplace structures. At the smaller, more human scale, however—in the realm of private homes and commercial spaces—the look of new Riyadh is far more impressive.

Even as technology has led to a homogenization of values, photo sharing on social media platforms have nevertheless created powerful aesthetic niches, making people value smart, artfully-considered design, enabling beauty to flourish in unlikely places. The result, in Riyadh, is a city that is imminently Instagrammable: from the large public works projects to the tiny flower shops, coffee shops, residences, and even strip malls.

Unlike other places that have developed rapidly as luxury destinations for tourists, the most interesting and impressive buildings aren’t the glitzy, foreign flagship stores erected by international conglomerates; they are the wave of new, locally-owned restaurants and shops popping up throughout Riyadh’s neighborhoods. For small business owners especially, a widespread desire to build something with uniqueness and elegance is a sign of civilizational optimism more authentic than any poll.

The weather in winter was mild but sunny and warm, very much like the pleasant Miami Beach climate where I live. Going from a place that, like Florida, is brimming with optimism is both infectious and heartening. In a world that seems to be spinning out of control with ever more decadence and the flattening of history and tradition that accompanies inter-connectedness, the kind of positive change I found in Saudi Arabia is both surprising and welcome.

Today, the Kingdom is attempting to navigate the technological and economic advances of 21st Century life while maintaining a measure of their distinct history and culture against a technocrat-led, homogeneous Western monoculture that seems to bring with it so much ideologically Progressive baggage.

As the Kingdom changes, the question of the inevitability of liberalism necessarily leading to vice and libertinism is in the back of people’s minds. Saudis of all backgrounds—from shopkeepers, students and housewives to government officials and educated professionals—wanted to talk to me about the woke race and gender obsession that has engulfed America in recent years.

Their tone wasn’t one of judgemental disgust, but of horrific shock. Is this, they might ask, the price of modernity and freedom? The interconnectedness of social media brings this concern home for ordinary Saudis as much as it must for its leadership.

Resisting this tide is a matter of a secure national or cultural identity more than individual morals. What’s required is an identity that is at once strong enough to withstand the onslaught of smartphone-delivered decadence, but also appealing and realistic enough to engage millions of its citizens who don’t want to abandon all the advantages and comforts of the outside world.

This is the great challenge for many countries, especially in the west, as they navigate a modernity that seems determined to self-destruct. Almost uniquely, however, Saudi Arabia seems to grasp the importance of revitalizing its national identity and, for that reason, is far better positioned to succeed.

Note: A much shorter version of this piece appeared originally in Newsweek.

This is amazing!

Wow. Eye opening article. This deep and fast of a change seems unlikely and potentially destabilizing. Is this solely MBS driven? Any signs of real push back from the prior establishment?